The Anatomy of Human Appearance and Movement

Whether you are an artist or student of anatomy, once you understand the concept of dermal-fascial tethers that define our body as a collage of spaces, contours and creases, you will begin to notice these attachments everywhere.

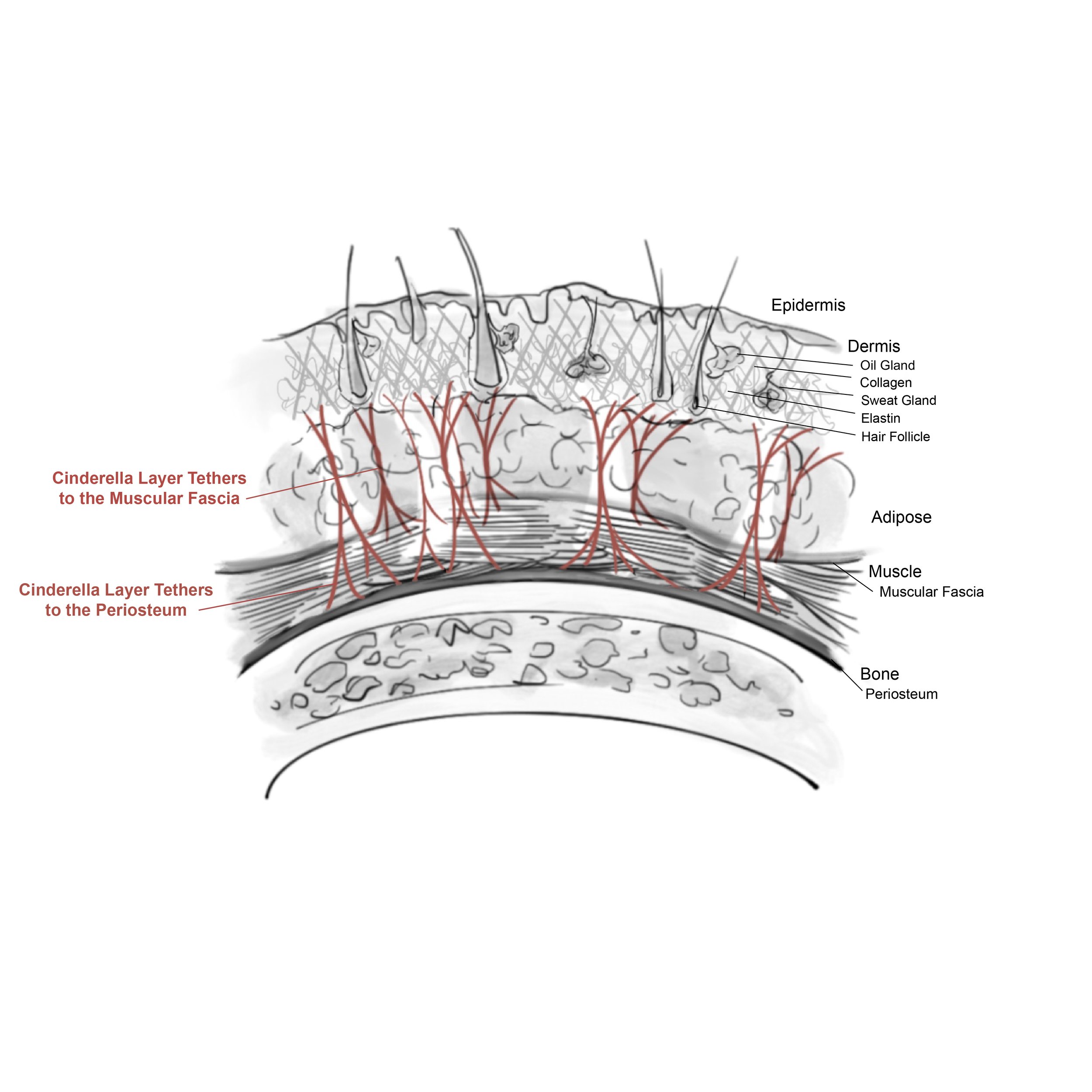

● Skin is held by a series of invisible tethers we will call the subcutaneous endoskeleton or Cinderella Layer.

● It might be considered the third layer of the skin because it is attached to the dermis.

● Like muscles, the tethers that make up the endoskeleton have an origin and insertion. The origin is typically the muscular fascia and/or the bony periosteum. The insertion is the dermal layer of the skin.

● The matrix of tethers coursing through the dermal-fatty-fascial space gives each of our bodies a unique outward appearance.

● The skin envelope, including this important third layer, also serves as a regulatory force helping to facilitate and regulate our movement.

● After tissue injury, it is critical for the surgeon and therapist to preserve, reinforce or re-create these tethers to help regain normal appearance and mobility.

“There are many things near us that we never notice simply because of the way we see. The way we look at things has a huge influence on what becomes visible for us.”

— John O’Donohue, ‘The Invisible Embrace, BEAUTY’

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to elucidate the anatomical attachments between skin and fascia that determine to a large degree how we look and move. Although these dermal-fascial tethers are contained within the vilified fatty layer, they are much more than just fatty septae. We call this subcutaneous endoskeleton the Cinderella Layer for its overlooked beauty and intelligence. During much of my 40-year professional career, I treated people with major burn injuries. Each year, 11 million burn survivor bodies worldwide are melted by fire and then hardened into immobility and anonymity by scar. Within these metaphoric blocks of stone is imprisoned our dynamic Cinderella Layer. Correction of deformity and disability requires a clear picture of the normal anatomy. Practitioners worldwide are already very interested in the fascia that connects our human tissues. Including the Cinderella Layer in this conversation is a crucial addition to the story.

In the spirit of John O’Donohue’s message above, we zoomed our focus in and out on this anatomical layer, not just as scientists and surgeons, but as evolutionary philosophers seeking to understand the purposefulness of nature. The Cinderella Layer is beneath the skin and therefore not readily seen. It is however responsible for our unique contours, folds, and symmetry. Tension and elasticity conducted through these tethers helps keep in check and balance the movement of our underlying muscular and bony skeleton. Many artists and bodyworkers have undoubtedly related body appearance and movement to unseen structures beneath the skin. We are merely shining a light on something right in front of us.

For the first time, the Cinderella Layer will be highlighted in its entirety, existing and functioning in every square centimeter of the body. We will marginally touch on interrelationships between the Cinderella Layer and clinical injury and surgery; however, our primary focus is to introduce a new way of looking at the human body to surgeons, artists, anatomists, bodyworkers, pathologists, evolutionary philosophers, and otherwise curious people. Through prose and illustration, we will demonstrate the interdependence of form and function when analyzing the human body. Some will see it as an “Ah-Ha” moment, and all, I hope, will immediately begin to see and treat the human body differently.

Historical anatomy texts peel away the skin to look at the muscles, then peel away the muscles to look at the bones. Other diagrams illustrate our major nerves, blood vessels and internal organs. The Cinderella Layer, consisting of attachments between the dermis and the fascia and/or periosteum is either left out entirely or loosely referred to as connecting fibers or septated fat. Surgeons have mostly focused on releasing these connecting fibers and removing or lifting fat to improve appearance. We will show how critical this layer of anatomy is to our human form and function.

The dermis is the deeper or second layer of our skin containing collagen for strength and stretchability, elastin for recoil or snap-back to resting skin tone, and other elements that produce lubrication, sweat, oil and hair. Although some like to consider every tissue in the body as a type of fascia, the fascia we are referring to is composed of relatively inflexible collagenous sheets that separate tissue planes beneath the skin and surround our muscles. Periosteum is dense connective tissue attached to and nourishing bone. As we reveal the collagen attachments that traverse the layer between the dermis and the fascia, and in some cases periosteum, they might be considered the third layer of the skin, beneath but wholly interactive with the dermis.

Both the fat and fascial-dermal attachments making up the Cinderella Layer serve important functions. The tightness, length and density of the collagen tethers and the amount of fat running through them varies with age, gender and ethnicity. What makes a person look fat or thin, old or young, round-faced or drawn, is the interrelationship between the fascial-dermal tethers and fat. It creates each person’s unique appearance. The subcutaneous fatty layer also functions to help facilitate glucose metabolism, temperature regulation and tendon gliding.

Ligaments typically attach two bones to stabilize a joint while allowing motion. The attachments of the skin to the underlying fascia, muscles and bones are like ligaments, but to avoid confusion, let’s call them tethers. Like ligaments, they stabilize and allow variable amounts of motion depending on how flexible, long and thick they are. With movement, these anchors provide leverage, protect you from hyperextension and rotational injuries, and elastin tethers bring your skin and body back into a resting posture and tone after stretching.

Try looking at your skin like a sheath surrounding a tree with the bark being the epidermis or outer layer of the skin. The knotty contours just beneath the bark would be your dermis, and in some cases, scar tissue. The roots of a tree extend into the ground, often surrounding large stones lending support to stand and withstand the forces of gravity and nature. Your skin is likewise tethered to the fascia and sometimes bone. This adds rooted durability and resiliency to your appearance as well as flexibility with movement. Your Cinderella Layer also contains vascular and lymphatic connections to the dermis, which like the roots of a tree, nourish your skin.

We have come to realize how important the neglected Cinderella Layer is when the dermal-fascial tethers become attenuated and lengthened by chronological aging. Gravity and gradual degradation of collagen and elastin over time are responsible for many of the changes in our appearance as we age like jowls, sagging medial thighs and a double chin.

In the case of soft tissue injury including surgery, normal healing leads to scar tissue formation that invariably shortens over time. This is called secondary contraction. Visible skin scarring is often the tip of the iceberg, with subcutaneous fascial and muscular tightness being more disfiguring and debilitating. Scars under tension thicken and shorten even more (hypertrophic scars) because the body is sensing a need to increase the amount of scar tissue laid down to prevent tearing or ulceration. Contraction may lead to pathologic contractures (tight, deforming cords limiting mobility) when scars cross joints or bridge different spatial planes. For example, second degree or partial-thickness burns on the face usually heal smoothly except in areas of tissue tension like the jawline, where thick, hypertrophic scars typically form due to strain on the skin from chewing, talking and head movement.

Therapists are caught between wanting to stretch underlying muscles and joints, and not wanting to contribute to excessive scarring of the skin and Cinderella Layer by adding tension. Thoughtful, gradual stretching, while simultaneously reinforcing either manually or with a splint the anchoring tethers separating planes of motion, will minimize deleterious scar tension and shortening.

We are born with anchoring tethers that purposefully serve as fulcrums for expansion and contraction. These anchors, when preserved or reconstructed after injury, help to prevent excessive scarring and neutralize non-purposeful tension. A surgeon might obliterate anchoring tethers without considering that a well oriented skin graft or scar can help to re-create their evolutionary design. Loss of normal skin-fascial attachments, whether it be accidental or iatrogenic (medically or surgically induced), wreaks havoc on the way we look and the way we move.

We divide the Cinderella Layer tethers into descriptive, functional categories depending on whether the attachments between the dermis and the fascia serve more as boundaries, anchors, animators, accordion-like or elastic band frameworks. In most areas of the body, the tethers serve more than one of these purposes. A few of these complex areas will be addressed as separate cases. All tethers ultimately function to support our appearance and movement. As we proceed with a more in-depth description of The Cinderella Layer, look in the mirror, pull on your own skin, then feel and watch it recoil.